After the age of seventy death walks closely behind, scythe at the ready. Only a fool thinks otherwise. Everybody I know over about sixty-five has some sort of chronic health issue. We suffer from various aches and pains that seem to wax and wane with the weather, and most have hypertension, and soreness and stiffness from old injuries. Most conversations with people our age eventually devolve into “organ recitals” — a litany of our infirmities, impairments, surgical procedures, and pharmacopeia.

The actuarial tables don’t lie, and very few over the age of seventy are physically or mentally up to new challenges. Although more of us live longer, we’re not necessarily living healthier. Many are overweight, and most out of shape. Medical science keeps us out of the morgues a little longer, but human biology has not changed. The most reliable way to predict your life span, assuming you don’t slip on a banana peel and break your skull, or get in a car wreck, is to see how long your ancestors lived — a good reason to do some genealogy.

It’s time to write my memoirs or autobiography if I’m going to do it. Why do that if you’re not famous? Not many readers are interested in the lives of the not-famous or infamous. But I think there are several good reasons, besides hubris, to leave a first person written account of your life, even if you don’t publish it. Aside from the value to future historians who may be researching our era, a firsthand record of your life is perhaps the most valuable thing you can leave your descendants, unless you are wealthy — then leave money and property!

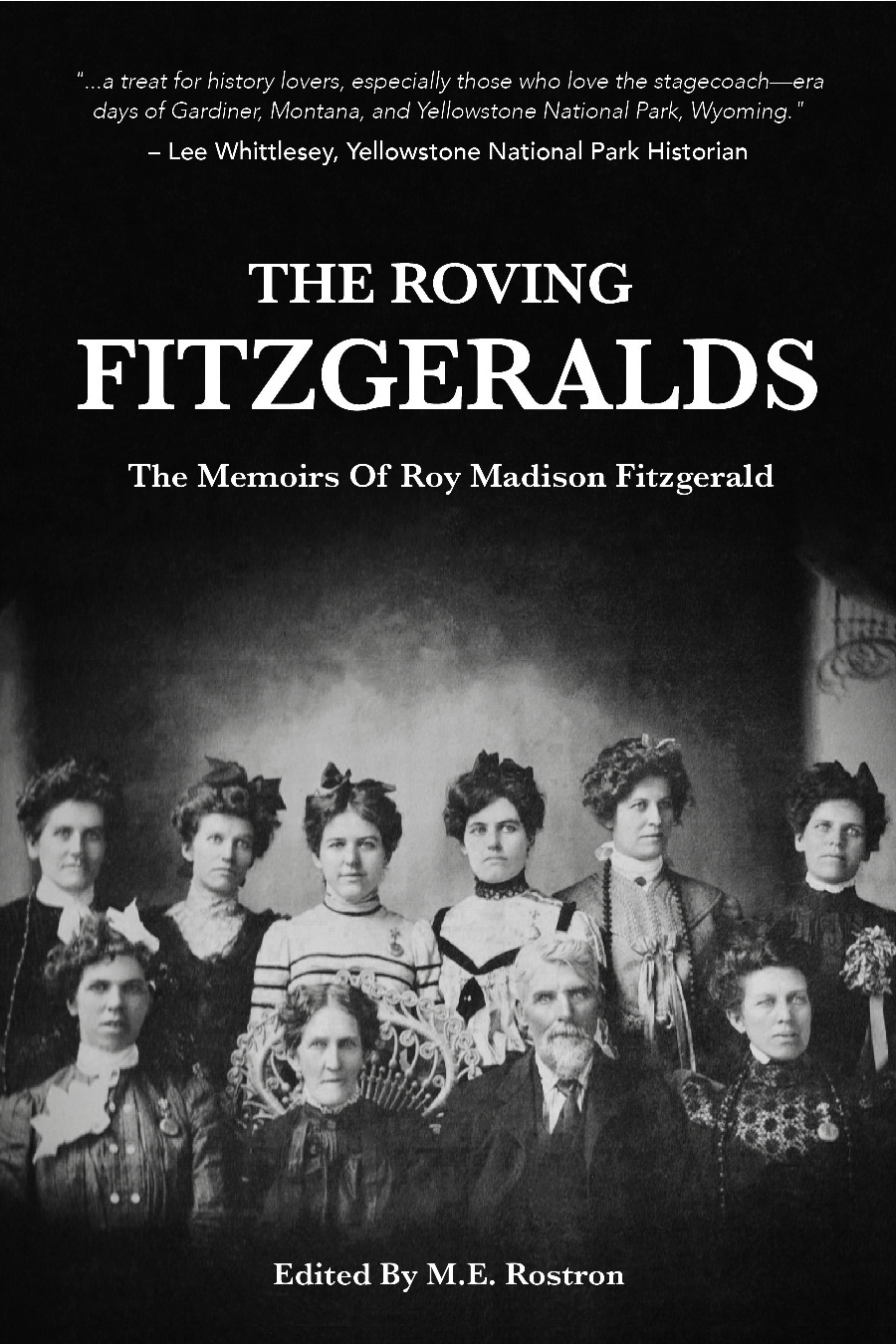

Rediscovering my great grandfather’s long lost writings was a remarkable event, and the year long editing and researching prior to publishing the book was fascinating. (“The Roving Fitzgeralds,” 2021.) The months I spent preparing the book for publication led me down many paths, intellectually and emotionally. I connected with my family history in ways I hadn’t before. I experienced a sense of what it was like to live in the era before all the mechanical and electronic gadgets we take for granted existed.

I wish more of my ancestors had written about their lives. It would be wonderful to have Selleck or Mary Fitzgeralds’s first hand notes on their wagon train trip from Iowa to California in 1862, and their subsequent travels by horse and wagon to Oregon and Montana. I wish Selleck’s grandparents would have left a first hand record, even a diary or journal, of their immigration from Ireland to Virginia in the 1740s. Alas, I know of no written records other than Roy Fitzgerald’s from either side of my family.

I’ve never been a fan of the sort of confessional or tell-all memoirs that often make the bestseller’s lists. I’m not very interested in Einstein’s sexuality or relations with women, but I am fascinated with his intellectual development, his breakthroughs in physics, his interactions with other scientists, politicians, and his ties to the Manhattan Project.

If I decide to write an autobiography or memoir, I’ll approach the project much as my grandfather, Roy Fitzgerald did. His intention was to relate the most notable incidents in his life, and to give the reader a sense of what it was like to be alive during those years, while imparting interesting information about the history of Yellowstone Park, Montana, Nevada, and Oregon, during an era when the the automobile was replacing the horse, and the phone, rails, and roads were connecting the West to the rest of the world. Considering that Roy dropped out of school after the eighth grade, he did a nice job of it. I would be happy to do as well.

Roy’s memoirs almost didn’t get written. He began writing when he was in his early eighties, and died at the age of eighty-seven. It was a near thing, as his health was failing, but he still managed to make several trips from Oregon to Montana to verify his memories of some of the events he recalled from his youth in Gardiner. He barely lived to finish his memoir, and did not live to see it published.

I don’t want to make that same mistake, and it’s certainly not given that I will be mentally or physically capable of writing my memoirs or autobiography in the future. So I’d best be about it, and so should you if you’re over sixty-five, because seventy-three will never be the new forty-three!